Fees, Resource Limits, and Metering

Fees overview

Stellar requires a fee for all transactions to make it to the ledger. This helps prevent spam and prioritizes transactions during traffic surges. All fees are paid using the native Stellar token, the lumen (or XLM).

There are two types of fees on Stellar:

Resource fee: only applies to smart contract transactions. The amount the submitter must pay for their transaction to execute. This amount is based on a transaction’s resource consumption and the state of network storage (described in the Storage Dynamic Pricing section). Read about resource fees below.

Inclusion fee: the maximum amount the submitter is willing to pay for the transaction to be included in the ledger. Read more below.

When competing for space on the ledger, smart contract transactions are only competing with other smart contract transactions, and transactions that do not execute a smart contract are only competing with other transactions that do not execute a smart contract.

The lumens collected from transaction fees go into a locked account and are not given to or used by anyone.

Resource fee

All smart contract transactions require a resource fee in addition to an inclusion fee:

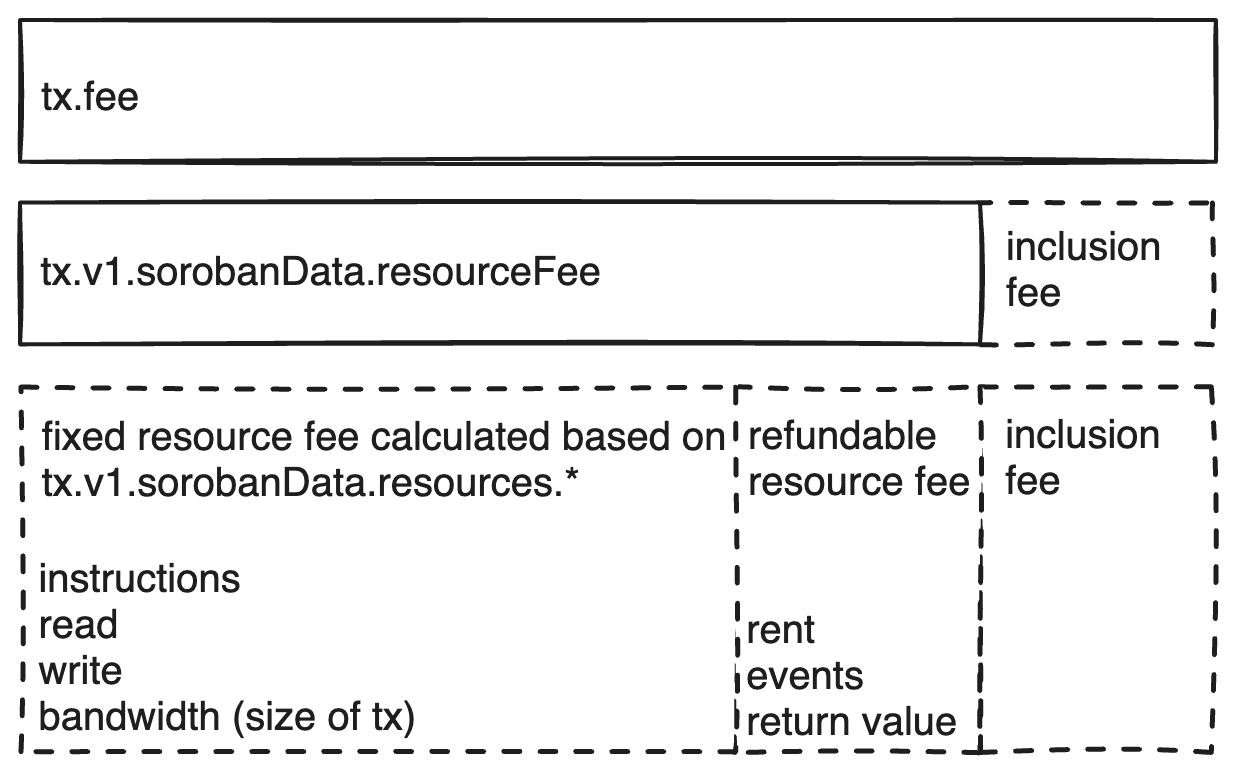

Transaction Fee (Tx.fee) = Resource Fee (sorobanData.resourceFee) + Inclusion Fee

Transactions that do not execute a smart contract can be thought of as having a resource fee of zero (resourceFee == 0). Conversely, for smart contract transactions, you can subtract the resource fee from the total transaction fee to derive the equivalent classic transaction fee component, which is the inclusion fee.

* Diagram: Solid line boxes are what is actually present in the transaction, while dotted lines are derivable.

* Diagram: Solid line boxes are what is actually present in the transaction, while dotted lines are derivable.

Smart contracts on Stellar use a multidimensional resource fee model that charges fees for several resource types using network-defined rates on the Stellar Lab. The resource fee is calculated based on the resource consumption declared in the transaction and can fluctuate based on a mutable storage write fee (more on that in the Storage Dynamic Pricing section below). If the transaction attempts to exceed the declared resource limits, it will fail. If the transaction uses fewer resources than declared, there will be no refunds (with a couple of exceptions).

The resource fee depends on the following resources:

- Instructions: the number of CPU instructions the transaction uses, metered by the host environment;

- Ledger entry accesses: reading or writing any single ledger entry (any storage key in the contract context);

- Ledger I/O: the number of bytes read from or written to the ledger;

- Transaction size: the size of the transaction submitted to the network in bytes;

- Events & return value size: the size of the events produced by the contract and the return value of the top-level contract function — both events and return value are included in transaction metadata;

- Ledger space rent: the payment for the ledger entry TTL extensions (i.e., rent payments) and rent payments for increasing ledger entry size. Refer to the state archival section for more information about smart contract rent.

Some parameters may contribute to multiple fee components. For example, the transaction size is charged for network propagation (as network bandwidth is limited) and for historical storage (as storing ledger history is not free).

The implementation details for fee computation are provided by the following library. This library is used by the protocol to compute the fees and thus can be considered canonical. The resource fee rates may be updated based on consensus from the network validators.

Find current resource fees in the Resource Limits & Fees on the Stellar Lab.

For help in analyzing smart contract cost and efficiency, see this How-To Guide.

Refundable and non-refundable resource fees

The resource fee is calculated with a non-refundable fees portion and a refundable fees portion: ResourceFee(sorobanData.resourceFee) = Non-refundable resource fee + Refundable resource fees.

Non-refundable fees: calculated from CPU instructions, read bytes, write bytes, and bandwidth (transaction size, including its signatures).

Refundable fees: calculated from rent, events, and return value. Refundable fees are charged from the source account before the transaction is executed and then refunded based on actual usage. However, the transaction will fail if refundableFee is not enough to cover the actual resource usage.

Find a transaction’s resource fee

The best way to find the required resource fee for any smart contract transaction is to use the simulateTransaction endpoint from the RPC, which enables you to dry run the execution of a transaction to compute the necessary resource values and fees.

Resource limitations

Only smart contract transactions are subject to resource limitations.

Stellar’s ledger close time is constrained to a few seconds, preventing the execution of arbitrarily large transactions, regardless of the resource fees involved. All resources mentioned in the prior section are subject to a per-transaction limit. A transaction’s memory (RAM) is also capped, though not subject to any charge.

Resource limits are determined by a validator vote and can be adjusted based on network usage and ecosystem needs with a validator consensus.

Find current resource limits in the Resource Limits & Fees on the Stellar Lab.

Inclusion fee

The inclusion fee is the maximum bid (a bid denotes a dynamic fee, meaning it varies based on certain network conditions) the submitter is willing to pay for the transaction to be included in the ledger. The inclusion fee equals the number of operations in the transaction multiplied by the effective base fee for the given ledger: inclusion fee = # of operations * effective base fee

Effective base fee: the fee required per operation for a transaction to make it to the ledger. This cannot be lower than 100 stroops per operation (the network minimum).

Stroop: the smallest unit of a lumen, one ten-millionth of a lumen (.0000001 XLM).

Transactions can have up to 100 operations per transaction except for transactions that execute a smart contract. Smart contract transactions are only allowed one operation per transaction (unless the transaction is getting fee-bumped; this would add another operation), and the limits are instead specified in CPU instructions and other resource limits.

When you set a base fee for a transaction, you are specifying the maximum amount you are willing to pay per operation in that transaction. This doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll pay that amount. You’ll only be charged the lowest amount needed for your transaction to make it to the ledger. If network traffic is light and the number of submitted operations or transactions is below the network ledger limit (configured by validators: currently 1,000 non-smart-contract operations and 100 smart contract transactions), you will only pay the network minimum (configured by validators, currently 100 stroops).

Alternatively, your transaction may not make it to the ledger if the effective base fee is higher than your base fee bid. When network traffic exceeds the ledger limit, the network enters into surge pricing mode, and your effective base fee becomes your maximum bid.

Fees are deducted from the source account unless there is a fee-bump transaction that states otherwise. Learn about fee-bump transactions in the Fee-Bump Transaction section.

Surge and dynamic pricing

Surge pricing

The network can enter surge pricing mode under two circumstances: 1. when the number of operations submitted to a ledger exceeds the network capacity (1,000 operations for transactions that do not execute smart contracts), or 2. if there is competition between smart contract transactions for a particular resource (instructions, ledger entry accesses (reads and writes), ledger IO (bytes read and bytes written), and the total size of transactions to be applied). During this time, the network uses market dynamics to decide which transactions to include in the ledger. Transactions that offer a higher maximum base fee bid make it to the ledger first.

During surge pricing mode, transactions are sorted based on their inclusion fee amount, and the user pays the minimum inclusion fee in their transaction set. For example, if there are five transactions with respective inclusion fees of 2, 3, 4, 4, and 5 XLM, and only four of them an make it to the ledger, then all included transactions pay the inclusion fee of 3 XLM. If all five transactions can make it to the ledger (which would mean the network is not in surge pricing mode), each would pay the minimum inclusion fee of 100 stroops (.00001 XLM).

If there are multiple transactions offering the same inclusion fee, but they cannot all fit into the ledger, transactions are picked randomly so that the total operations for the entire set don’t exceed 1,000. The rest of the transactions are pushed to the next ledger or discarded if they’ve been waiting for too long. If your transaction is discarded, it will never appear in a ledger as retrieved from RPC.

It is recommended to apply ledger bounds or time bounds to transactions — either your transaction makes it to the ledger or fails, depending on your time and/or ledger parameters.

You are more likely to pay a higher inclusion fee when submitting smart contract transactions. Smart contract transactions have tighter ledger limits than transactions that don’t interact with smart contracts and will therefore experience surge pricing more often. You are more likely to pay your maximum inclusion fee bid or, at least, the minimum inclusion fee bid in your transaction set. So, you must plan your fee bidding strategy accordingly.

Dynamic pricing for storage

Stellar’s storage database size is determined by two forces: the rate of additions (writes) and the rate of deletions (evictions). Stellar has set a ledger growth threshold to a constant value (the BucketListTargetSizeBytes network parameter, implemented to prevent explosive state growth and subject to change based on validator vote). Because there is a fixed capacity, write fees are based on the ledger size and can alter dynamically based on that size.

When the ledger size is large, there is a higher demand for storage space, which causes a higher write fee. Over time, entries are archived, reducing the overall ledger size and, thereby, reducing storage pricing. This fee model is designed as if the database size represents the current demand for storage at any given instant.

Write fees will grow gradually over time when the database size is below the ledger growth threshold and will grow linearly, but with a 1,000x factor after exceeding that threshold. This is a safeguard against spam and is not anticipated under normal circumstances.

Metering

Metering is a mechanism in the host environment that accounts for the resource costs incurred during the execution of a smart contract. The outcomes of metering act as the canonical truth of a smart contract’s execution cost and serve as an input for fee computations.

Stellar’s smart contract execution environment comprises a host and a guest. The host encapsulates shared functionalities for all contracts, including host objects, functions, and a Wasm interpreter (VM). The guest environment is where the compiled Wasm contract is interpreted and executed. A detailed discussion of these environments can be found in Environment Concepts.

The division between the host and guest environments and their shared functionalities necessitates a unique approach to resource accounting. In particular, the resources required for executing Wasm instructions and running host functions must be accounted for uniformly, with costs in terms of CPU instructions and memory bytes.

Consider two contracts: A and B, both comprising the same number of Wasm instructions. If Contract A repeatedly calls host functions for complex computations while Contract B executes pure arithmetic operations within the VM, Contract A should be more costly, and this difference should be accurately represented in the metering process.

Metering ensures fairness, thwarts resource manipulation and attacks, and generates a deterministic and reproducible measure of runtime resource costs.

Methodology

To maintain equivalence in metering between the host and guest, computation costs on both sides are expressed in terms of CPU instructions and memory bytes (representing CPU and RAM usage). Metering and limit-checking occur within the host environment, and pre-calibrated numerical models ensure results are deterministic.

Cost types

Metering is segmented into host components, referred to as cost types. Each cost type can be viewed as a “meta instruction” symbolizing a specific host operation with a known complexity that depends on a runtime input. For instance, cost type ComputeSha256Hash represents the cost of computing the SHA256 hash of a byte array.

Execution of Wasm instructions is accounted for as a host cost type WasmInsnExec, which has a constant CPU cost per Wasm instruction. This methodology treats guest instructions and host executions equivalently.

Find a complete list of host cost types and their definitions here: ContractCostType.

Cost parameters

Cost types are carefully selected to:

- Serve as comprehensive building blocks for all significant contract execution costs;

- Ensure each component cost increases at most linearly (i.e., constant or linear) with respect to its input. That is,

y = a + bx, whereyis the cost output,xis the input, anda&bare the constant and linear model parameters, respectively.

Each cost type has a separate model for both resource types (CPU and memory).

The parameters for each model, a and b, are calibrated and fitted offline against inputs of various sizes. The collection of all model cost parameters from the network configurable entries (see ConfigSettingsEntry can be updated through network consensus.

Metering process

Before contract execution, the host environment is prepared with the cost parameters and a budget defining the resource limits. Metering is then implemented to measure the cumulative resource consumption during host execution.

During execution, whenever a component (a code block defining a cost type) is encountered, the corresponding model computes the resource output from the runtime input and increments the meter accordingly. The meter checks the cumulative consumption against the budget limit. If the limit is exceeded, an error is produced, and execution is terminated.

If the contract execution concludes within the specified resource limits, the metered total of CPU instructions is recorded and utilized as the input for fee calculation. While memory usage is not included in the fee computation, it is nevertheless subject to the resource limits.

Inclusion fee pricing strategies

There are two primary methods to deal with inclusion fee fluctuations and surge pricing:

- Method 1: set the highest fee you’re comfortable paying. This does not mean that you’ll pay that amount on every transaction — you will only pay what’s necessary to get into the ledger. Under normal (non-surge) circumstances, you will only pay the standard fee even with a higher maximum fee set. This method is simple, convenient, and efficient but can still potentially fail.

- Method 2: resubmit a transaction with a higher fee using a fee-bump transaction

Set the highest fee you’re comfortable paying

In general, it’s a good idea to choose the highest fee you’re willing to pay per operation for your transaction to make it to the ledger. Wallet developers may want to offer users a chance to specify their own base fee, though it may make more sense to set a persistent global base fee that’s above the market rate since the average user probably doesn’t care if they’re paying 0.8 cents or 0.00008 cents.

Remember that you’re more likely to pay your maximum fee bid with smart contract transactions.

Fee-bumps on past transactions

Even with a liberal fee-paying policy, your transaction may fail to make it into the ledger due to insufficient funds or untimely surges. Fee-bump transactions can solve this problem. The following snippet shows you how to resubmit a transaction with a higher fee (as long as you have the original transaction envelope):

- JavaScript

// Let `lastTx` be some transaction that fails submission due to high fees, and

// `lastFee` be the maximum fee (expressed as an int) willing to be paid by

// `account` for `lastTx`.

server.submitTransaction(lastTx).catch(function (error) {

if (isFeeError(error)) {

let bump = sdk.TransactionBuilder.buildFeeBumpTransaction(

account, // account that will PAY the new fee

lastFee * 10, // new fee

lastTx, // the (entire) failing transaction

server.networkPassphrase

);

bump.sign(someAccount);

return server.submitTransaction(bump);

}

// ...other error conditions...

}).then(...);

Suppose you submit two distinct transactions with the same source account and sequence number; the second transaction is a fee-bump transaction. In that case, the second transaction will be included in the transaction queue, replacing the first transaction if and only if the fee bid of the second transaction is at least 10x the fee bid of the first transaction.

This value can typically be found in the fee_charged field of the transaction response under the tx_insufficient_fee error case.